“Someday, after mastering the winds, the waves, the tides and gravity, we shall harness for God the energies of love, and then, for the second time in the history of the world, man will have discovered fire.”

— Teilhard de Chardin

The life of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin is fascinating, even apart from the issues it breaks open for public discussion. A drama of personal awakening, search for meaning, scientific adventure, unresolved conflict with authority, and human love, it provides a perfect vehicle to engage viewers of every age.

The television story is told largely in the words of Teilhard himself, with comments from his friends and superiors, all taken from some 30 volumes of books, , letters, and personal journals. Visuals include locations where he worked and lived as they are seen today, along with embedded black and white images from substantial archives of photos and film. Key moments are dramatized in evocative close-up, with frequent imagery of gestures and actions blended with documentary coverage to create a brisk visual pace. CGI is used to illustrate futuristic concepts. Interviews with experts provide context and commentary.

ACT 1 LOVING GOD VERSUS LOVING THE EARTH

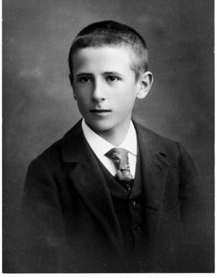

One would not guess from his early pious upbringing that Teilhard would one day be considered a dangerous revolutionary by his Catholic Church. A sensitive child, Pierre was born in 1881 to members of the rural French gentry. From his father, a chartiste — a trained naturalist — who took him on frequent hikes to collect rock and flora samples in the neighboring volcanic mountains, he absorbed a love of nature. From his mother, who home-schooled him, he developed a deep sense of Catholic piety. In addition to these formative influences, his own intense inner quest for permanence and meaning drove him from an early age.

Pierre did everything “right” as a youth. He became a model student in a Jesuit school, then became a Jesuit himself. In addition to his religious studies he took up geology, with a passion for fossil hunting and a commitment to science. In studying the evidence of geologic history, he began to see the sweep of deep history, which he applied to his understanding of the new field of evolution. Teilhard became so passionate about his scientific studies that he came to worry that his love for the earth might threaten his love for God. The resolution of this inner crisis was suggested by a religious mentor, who advised that he should seek God through the earth.

ACT 2 THE EVOLUTION OF TEILHARD

Taking this advice to heart, Teilhard became an avid collector of fossils in Egypt, where he taught Muslim high school students physics and chemistry for three years. His work captured the attention of the Paris Museum of Natural History, where he would later work. He went on to four years of theological studies on the southern coast of England, where he spent all his spare time seeking, finding , and meticulously labeling fossils of the Mesazoic era.

Shortly after his ordination in 1911, Teilhard began to see that the Christianity of his mother and his fellow Jesuits was unprepared to accommodate the insights of modern science, especially the theory of evolution. His Church, he believed, needed to reformulate its understandings — and he was prepared to help. Assisted in part by his mystical sense of divine presence permeating the earth, he recognized evolution not just in terms of changing species, but as a gradual emergence of the whole cosmos. He saw evolving human consciousness as a pivot point in this process that would be able to appreciate the past genesis of the universe and to assist the unfinished sweep of evolution emerging into a deep future. He believed this evolved evolution would richly enhance the understanding of God and God’s presence in history.

ACT 3 COMING OF AGE

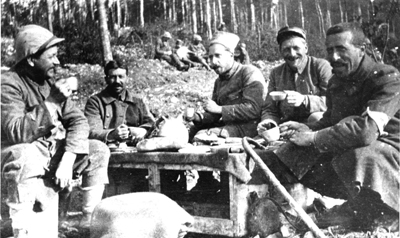

Soon the unspeakable horrors of World War I would challenge him to account in this theory for a God who tolerated such evil. The war created a crucible of urgency to make sense of it all. Called up to military service in 1914, he chose to serve in the trenches as a litter bearer with a brigade of North African Muslim troops rather than as a chaplain.

He performed heroically (and was twice decorated) during 67 battles over four and a half years, using every minute on break from the front to keep a journal and write numerous . He discovered in the camaraderie of his fellow soldiers a new sense of unity with humanity and an appreciation of other viewpoints. He was unaccountably drawn to the battlefield but was constantly afraid of dying because he saw thousands of men dying around him. He felt an urgent need to bring together his insights on God and evolution, sensing they would be important to others. His writings during the war contained the seeds of a prolific lifetime of writing, during which he continually refined his understanding of an essential union of cosmic evolution and the action of God.

ACT 4 ON THE TOP OF THE HEAP

Emerging from the war uninjured and with a new urbane confidence, Teilhard returned to his professional studies and soon achieved notice as a paleontologist on a fast track in the world of Paris’s Museum of Natural History. In Paris he reunited with a childhood playmate and cousin from the Auvergne region of France, Marguerite Teillard de Chambon. The head of a girls’ school and a successful single woman in 1920s Paris, she introduced him to intellectual salons where he was lionized. She was the first woman he loved other than his mother, and would remain one of his closest confidantes for a lifetime.

Teilhard passed his doctoral defense with the highest honors and the applause of a large group of lay people in attendance. He appeared to be rocketing to the top. But the theological implications of his evolutionary vision troubled some Church officials. After one lecture on evolution he was asked by a theologian about Adam and Eve. If evolution does not recognize them as historical, then what happens to the traditional doctrine of original sin? Teilhard provided a preliminary answer but readily agreed to put some further thoughts on paper. The course of his life was about to change.

ACT 5 A 20TH CENTURY GALILEO

Teilhard’s draft on alternative understandings of original sin disappeared from his desk while he was out one day. It would only reappear many months later when he was summoned by his Jesuit regional superior in Lyon. The paper had made its way to the Jesuit international headquarters in Rome. It left unhappiness in its wake. The story of Adam and Eve — their upending of God’s perfect creation and the introduction of evil into the world — was such a critical foundation stone in the edifice of organized Christianity’s understanding of redemption and of Christ as “the second Adam” that even today original sin remains a theological lightning rod. Teilhard thought he was re-interpreting the story in a way that that enabled the Church to speak to the modern world. The top Jesuit superior, Vladimir Ledochowski, believed he was choosing science over the bible.

With controversy swirling around him, Teilhard considered it an opportune moment to accept an invitation from a fellow Jesuit paleontologist to join his work in China, away from the lively debate he enjoyed in Parisian intellectual and religious circles. When Teilhard and Marguerite knelt side by side in a school chapel to say goodbye and pray for his safe passage, they had no inkling of the turn his life was about to take.

After spending a year in China, Teilhard returned to France and was summoned by his provincial superior, who directed him to sign a paper recanting his beliefs about original sin and promising not to write or speak on religious topics. This Teilhard could not do. He asked for time; he consulted friends. He wanted neither to leave the Jesuits nor to sign the document but sought negotiation instead. In the end he signed a modified document, agreeing not to publish without permission. He was also assigned permanently to China — in effect, into exile.

ACT 6 CLERICAL INDIANA JONES

In China a world of adventure awaited Teilhard, opening new horizons of fossil discoveries and professional success. In his first year he accompanied his fellow Jesuit, Emile Licent, on extended expeditions to areas ravaged by armed brigands. He was nevertheless in his element contending with the rugged demands of camping in the sere beauty of the Ordos desert and Eastern Mongolia. They returned with thousands of kilos of fossils to be examined and cataloged.

Sculpture of Teilhard the geologist by Marie Bayon de la Tour

Teilhard stayed in China for another twenty years but traveled frequently to its outlying areas and to the United States, Africa, India, Burma, Java, and other places. He became, in the estimation of the director of the American Museum of Natural History in New York, the world’s foremost expert on soil strata in Asia, the key to dating fossils. He became an active participant in an international gathering of expatriates doing archeological and paleontological digs in China, mostly funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. He was invited to join the world-famous trans-Asian Citröen expedition as the official geologist. A champion of China’s rights to fossils found on its soil, he was invited by Li Jie, the director of the newly founded Chinese Cenozoic Research Laboratory, to serve as the geologist on the team searching the Zhoukoudian region near Peking for human fossils. The result was the discovery of “Peking Man,” one of the early hominids considered a “missing link” in human evolution.

ACT 8 THE PHENOMENON OF MAN

From his first days in China, Teilhard found time to pursue his theories of divine energy suffusing all matter, creating the force of evolution. He wrote The Divine Milieu and sent it to France, but the Jesuits denied permission to publish. He wrote and rewrote his magnum opus, The Phenomenon of Man, which laid out a scientific case for his beliefs. That case posits that a degree of consciousness, or spirit, is innate even in the most primal spirit/matter of the “Big Bang;” that consciousness has evolved in plant life and animal life continuously to the point where human self-reflection initiates the experience of freedom and of love; and that it still continues to evolve, being drawn ultimately towards an “omega point” in the far distant future that shall be the perfection of spirit and love. Publication of The Phenomenon of Man was also refused by Jesuit superiors, despite repeated appeals.

ACT 9 HUMAN LOVE

While living in Peking, Teilhard met an American sculptor, Lucile Swan, a religious skeptic who had accepted a commission from the Cenozoic Laboratory in Peking. She would become his soul mate and his sounding board. He joined her for afternoon tea when his work was done every day while he was in Peking. Free to challenge his ideas, she also inspired him. Their close friendship blossomed into a deep love that became her great frustration. She could not understand why he professed love for her but would not leave the Jesuits and give himself entirely to her. They wrote frequently when he was not in Peking, and their published letters covering a 23-year period portray a poignant relationship.

Lucile was not the only woman in Teilhard’s life, however. Half a dozen women held claim to his special affections over the course of his life. Tall, charming, carrying an easy air of authority, he attracted women — and was attracted to them. He believed in love, albeit a love never separate from his cosmic vision of God. He wrote that love is the attractive energy that binds all reality together — from atoms to humans — and is the very expression of God. But love for him was not just a cosmic notion. He also was open to love as personal experience disciplined by chastity.

ACT 10 FINAL VERDICT

When Teilhard was finally able to leave China and return to France at the end of World War II he was offered a teaching position at the College de France and a position at the Museum of Natural History in Paris. He hoped that a new Jesuit Superior General in Rome would approve these appointments and relax his prohibitions against publishing. Teilhard was invited to Rome to make his case personally. But after arriving in Rome he was made to wait 30 days before seeing the Superior General, with whom he had only a brief conversation. A month later he received the verdict in a letter: he was not allowed to publish his books and was directed to accept neither the position at the College de France nor the position at the Museum of Natural History. Moreover, he was directed to leave France once again and to live in New York City.

ACT 11 NEW YORK EXILE

In New York Teilhard was offered a position with the Wenner-Gren Foundation to pursue paleontological research in Africa. He lectured at Columbia University and Harvard and continued to write unpublished , pursuing in his later years a theory of a coming emergence of the “ultra-human,” foreshadowing today’s global transhumanism movement. He died of a heart attack on Easter Sunday, 1955. With only two Jesuits attending, he was buried at the Jesuit novitiate near Poughkeepsie, NY (now the location of the Culinary Institute of America) . The name on his simple tombstone was misspelled.

POSTSCRIPT

Before he left France for the last time, Teilhard was persuaded by a local Jesuit superior to bequeath all his papers to a lay woman so they would lie outside the jurisdiction of the Jesuit order. He wrote a simple will putting them in the hands of his secretary, Jeanne Mortier. Immediately after his death she turned them over to a French publisher. In just a few years his main books were published and translated into multiple languages, making them international best sellers.